Following on from the de-mystification parts 1 and 2, here's a song-by-song summary of some of what I did.

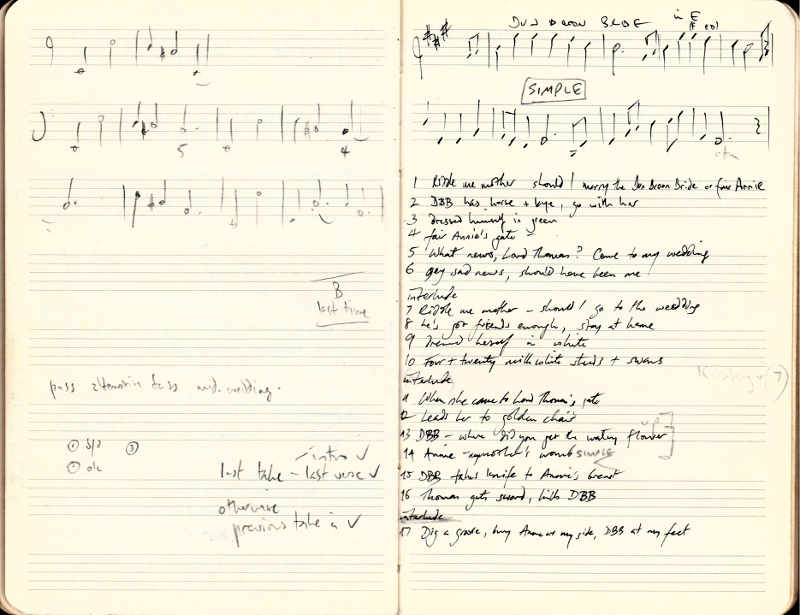

The Dun Broon Bride

Mixolydian in E (but we slowed the recording down to E flat and I had to learn it all over again to play it live).

I took the shape of the opening phrase and made that the bass riff for the first two lines: the first line has a 5th above it at the end, and the second one ends with a 4th, so that each line of the song ends with a slightly different harmonic trajectory.

At the bottom of the left hand page you can see the edit notes from the session: we did three takes, the first of which was a breakdown. The intro and the last verse were from take 3, everything else from take 2.

Johnny o’ the Brine

This is in a sort of hexatonic A minor with no 6th, but I put in a 6th anyway for an overall effect of the Dorian mode. It’s also played on the McNulty piano, and it’s also slowed down by a semitone after we recorded it. Unfortunately it’s just too slippery to play in G sharp minor, so live Ali has to sing it in A after all.

Again most of the piano playing is in three parts: two in the right hand, one in the left, as opposed to Dolly’s piano parts which are usually the other way round. The right hand parts mostly move in parallel fourths - one reason for this is that fourths are usually quite well in tune on keyboard instruments (in fact, in equal temperament they’re pretty good), whereas major thirds are just a catalogue of weird compromises.

After endless experiments with real and sampled bass drums, I played bass on this as well, aiming to channel Rick Kemp circa 1972 and missing by quite a long way. However, because we'd recorded the track to a click, we could give it to Julian Corrie (Miaoux Miaoux - now also of Franz Ferdinand) to do a great electropop remix, available on the Monorail remix CD Fake News.

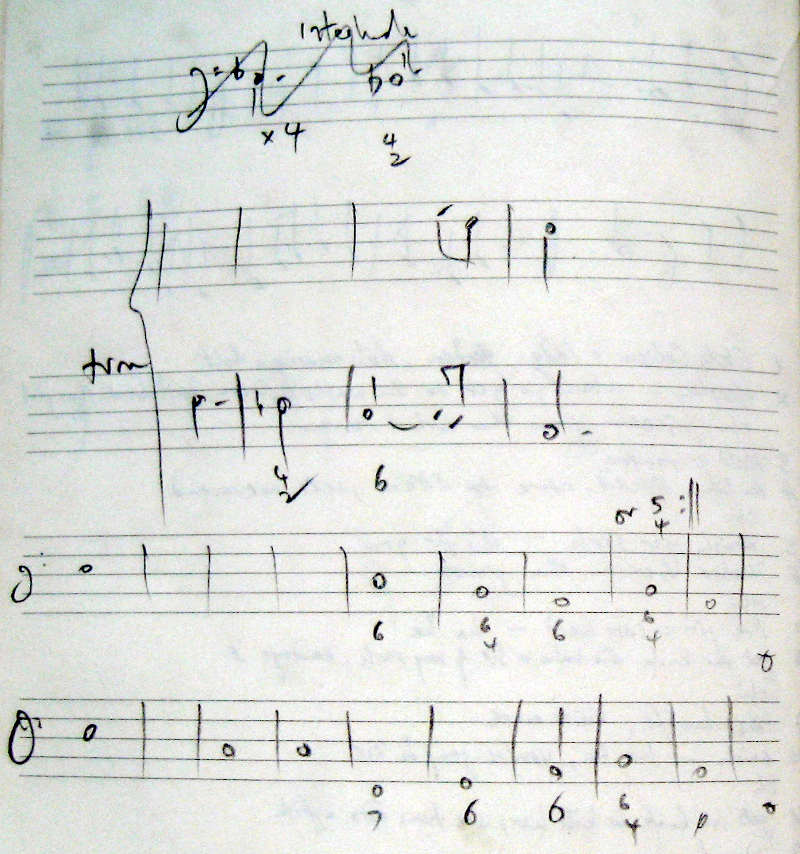

Young Johnstone

This tune is pentatonic, and so is pretty much everything I play while Alasdair is singing. The right hand just repeats an alternation of two chords all the way through, while the left hand wanders around the piano, sometimes almost doubling the voice, and at other times heading off to other places, while providing a slow-moving bass line. This one is on played on the Broadwood, with its very distinct and discrete registers. As well as a stereo pair on the piano, we added a separate bass end mic - in places it sounds like three different instruments, but there’s only one.

I hadn’t noticed that the quartal harmony in the interludes is rather reminiscent of The Blue Nile until Alasdair suggested we learn Easter Parade as an encore (from the album A Walk Across the Rooftops, beautifully recorded by Calum Malcolm), and the shapes seemed weirdly familiar.

Rosie Anderson

This tale of of the undercurrents of 19th-century gentility, with its Perth assemblies, called for a suitably genteel environment, so it seemed like a good time to get out the dulcitone, an invention of Glasgow’s Thomas Machell in the 1880s. It has a piano-like mechanism with hammers striking tuning forks which are set into a resonating soundboard, and this particular combination of metal and wood seems to blend happily with all sorts of other things. In 1917 it was advertised in The Scotsman as ‘The Fighting Man’s Piano’, as it could be shipped out to the Forces (at special discount rates) without going out of tune. Machell’s shop was at 45 Great Western Road, now a flyover for the M8 motorway.

This tale of of the undercurrents of 19th-century gentility, with its Perth assemblies, called for a suitably genteel environment, so it seemed like a good time to get out the dulcitone, an invention of Glasgow’s Thomas Machell in the 1880s. It has a piano-like mechanism with hammers striking tuning forks which are set into a resonating soundboard, and this particular combination of metal and wood seems to blend happily with all sorts of other things. In 1917 it was advertised in The Scotsman as ‘The Fighting Man’s Piano’, as it could be shipped out to the Forces (at special discount rates) without going out of tune. Machell’s shop was at 45 Great Western Road, now a flyover for the M8 motorway.

The song also called for some proper well-behaved genteel functional harmony: for an intro and interlude I’m using the falling bassline with a flattened 7th which first burned itself into my subconscious in the playout of Saucy Sailor at the end of Steeleye Span’s Below the Salt LP (1972, but I didn’t hear it till about 10 years later). I’ve already sneaked it into Robert Bremner’s version of Old Sir Symon the King on the Concerto Caledonia album The Red Red Rose, and here it is again.

Next time, Side 2.