(continued from part 1)

By this point, I had some interesting instruments to play, and I had the songs, but what was I going to play? I wanted the parts to be as simple and unfussy as possible - having played harpsichord a lot, it’s difficult to get out of the habit of playing an unfeasibly large number of notes - so I would have to start with direct, uncluttered ideas. I’d been bowled over by Dolly Collins’s keyboard arrangements that she composed and played for her sister Shirley: the Snapshots compilation album of live Shirley & Dolly Collins recordings made a huge impression on me after Sushil Dade left a copy on my desk when I was working at the BBC as a producer. Some time after this, Catherine Bott phoned me up with a tentative request that the two of us might perform some of those songs as part of a weekend that Shirley was programming at the South Bank in London. I think what I said was ‘Yes - I don’t care what’s in my diary, I’ll cancel it’. That weekend was my introduction to Shirley Collins, and also to Alasdair who was singing in another of the shows - he and Kate Bott got talking at the end of the weekend, after which Kate wrote to say ‘You two should meet’.

One reason I was excited to play Dolly’s keyboard parts was that I’d get to see what they looked like written down, and they are fascinating: in the summer of 2011, Katy Cooper and I spent three days in Shirley’s back garden, photographing the entire collection for posterity. Dolly had studied composition with Alan Bush at the Workers’ Music Association, and what appears simple on the surface often has some intricacy in its construction: Shirley told me that sometimes the material in the piano and organ parts was derived from the tune by a compositional procedure such as inversion or retrograde motion. The effect of this is to intensify the character of the tune: to make it more like itself rather than dressing it up as something else.

Another attraction of Dolly’s keyboard writing is that it tends to be in three parts, usually with an active part in the right hand above a two-part harmonic foundation. What it happily shares with Alasdair’s guitar playing is a general avoidance of (triadic tertial) chords, in the sense of ‘What are the chords for this tune?’ This question assumes that music from various traditions can (or should) be corralled into diatonic functional harmony. But what if there aren’t any chords? Or what if there’s just a bassline, as in most 18th-century Scottish fiddle music?

With Neil McDermott wielding microphones, we recorded all the piano and dulcitone parts in a couple of evenings over a weekend (26-27 October 2013), with me in the university concert hall and Alasdair singing on the other side of the door in the green room. I think about half of these guide vocals made it onto the record, but I can’t remember. On my way to the second session someone drove into the back of my car when I was only about 200 yards away - at least the dulcitone wasn’t in the boot at the time.

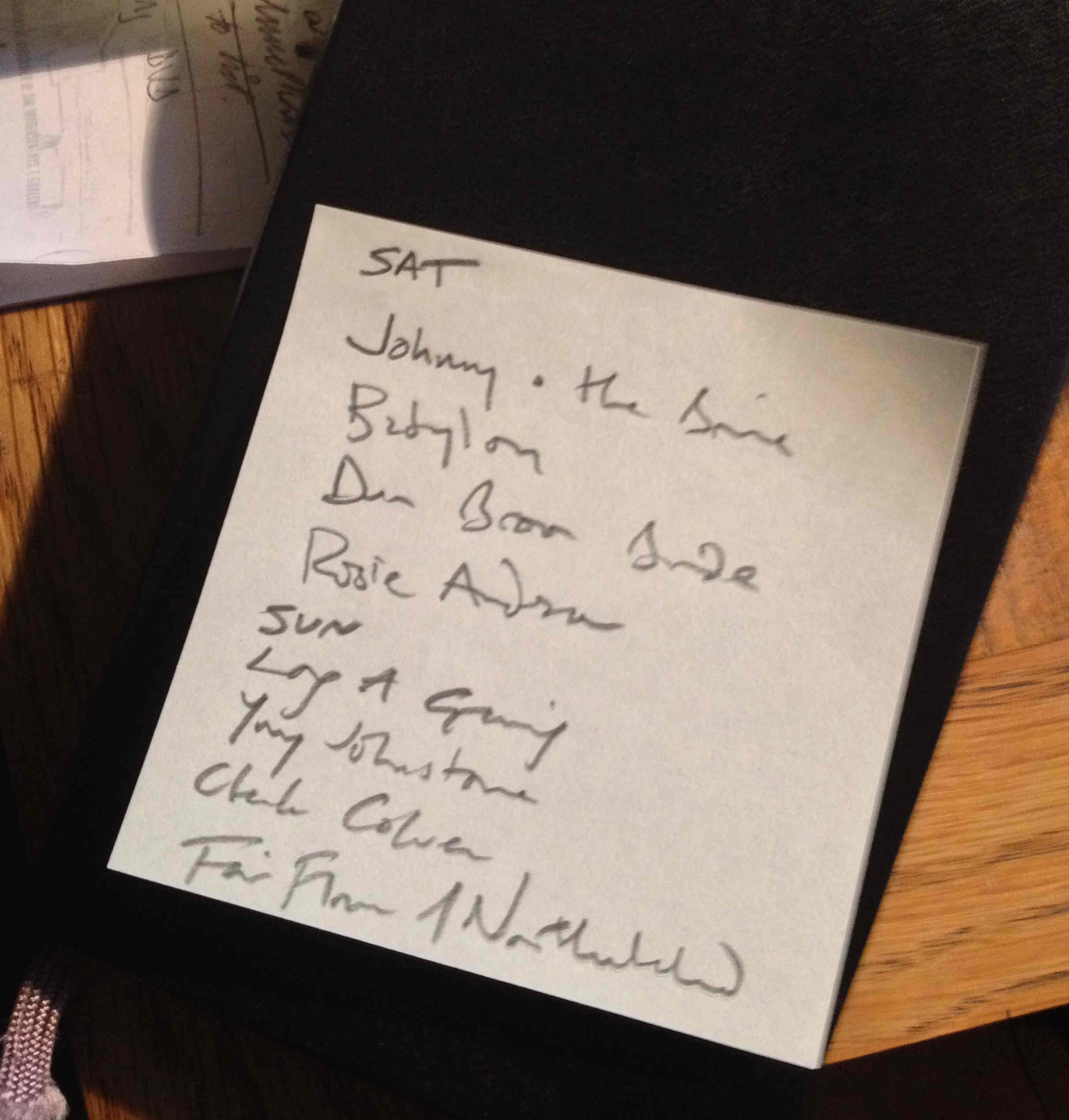

In the next instalment ... Side 1 of the LP track by track.