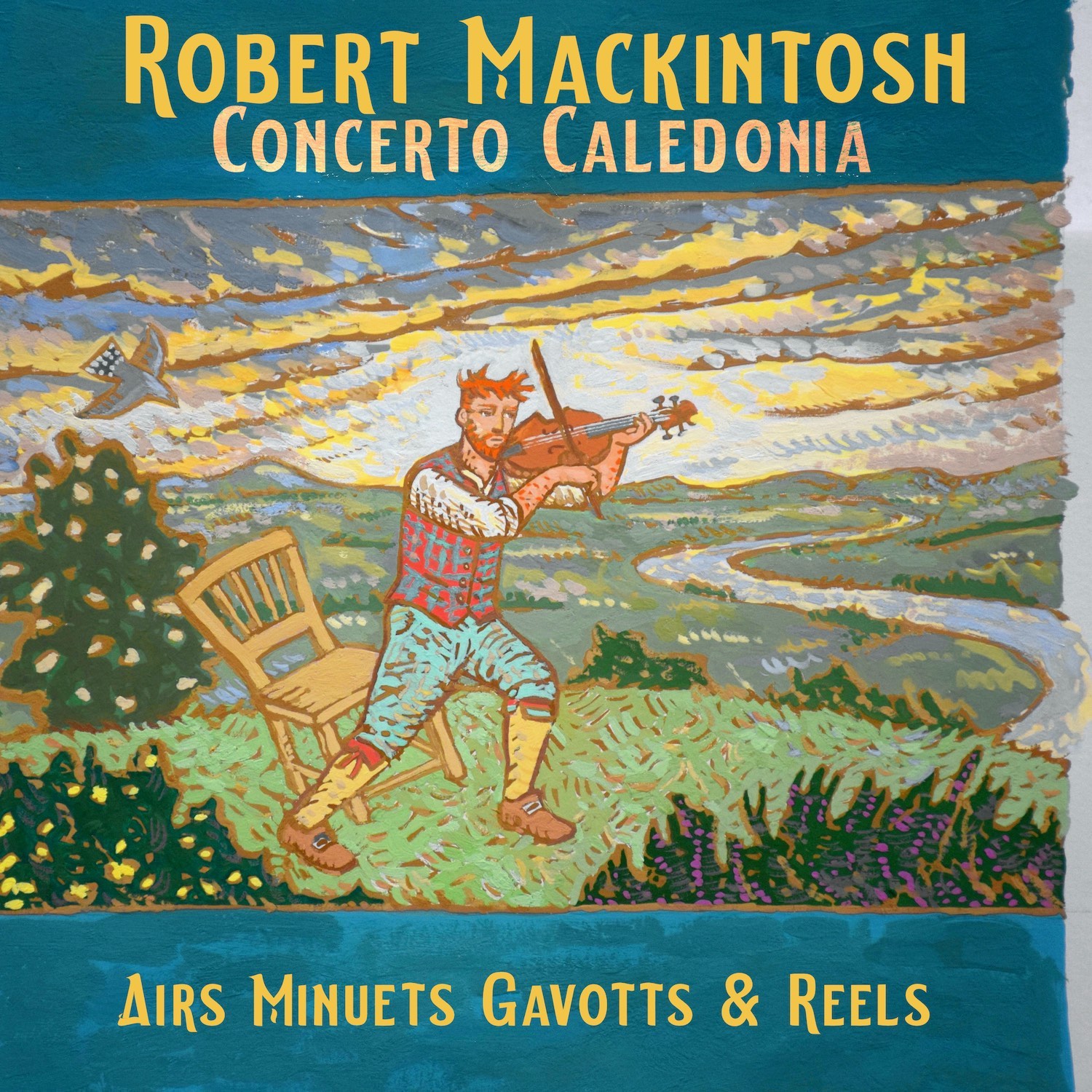

Airs Minuets Gavotts and Reels

David Greenberg, Greg Lawson, Alison McGillivray & David McGuinness explore the unrestrained variety ofgutsy reels, polite minuets, a virtuosic violin sonata, piano variations (played on an 1815 Edinburgh piano) and the sense of a life lived on the edge

![]() This is life-enhancing stuff – a disc guaranteed to put a spring into the heaviest, most jaded of steps.

This is life-enhancing stuff – a disc guaranteed to put a spring into the heaviest, most jaded of steps.![]() theartsdesk.com

theartsdesk.com

Is it folk?

Is it art?

You decide ...

David Greenberg - violin 1

Greg Lawson - violin 2

Alison McGillivray - cello

David McGuinness - harpsichord, square piano

Recorded on 5-8 June 2010 in Ardkinglas House, Argyll

Producer & Editor: David McGuinness

Engineer: Steve Portnoi

Mastering: Paul Baxter

Cover painting: Joe Davie

Design: Ewan MacPherson, Quiet Design

Square piano by Muir, Wood & Co., Edinburgh (no. 2089) c. 1815

Harpsichord after Moermans 1584 by Robert Deegan 1991

Thanks to:

David Sumsion & Angela Landon, Isabella & Sophie for letting us record in their house

Pieter Wispelwey, Lynne Bulmer for live gigs

The Harold Hyam Wingate Foundation who funded David McGuinness’s research fellowship at the University of Edinburgh, 2008-9

Everyone at University of Glasgow Music Department for rehearsal facilities and ProTools assistance, Allan Wright for tuning, and our families for letting us out to play

Robert Mackintosh (‘Red Rob’) (c. 1745–1807)

Airs, Minuets, Gavotts and Reels (1783)

1 Capt. Macduff’s Delight / Miss Katty Troter’s Reel

2 Minuetto (4)

3 Miss Grant of Grant’s Reel

4 Miss Grace Stewart’s Minuet

5 Gavotta (6)

6 Air (26)

7 Lady Helenora Home’s Reel / Miss Jessy Dalrymple’s Reel / Miss Stewart’s Reel / Miss Carre’s Reel

8 The Duchess of Gordon’s Delight*

9 Miss Campbell’s Reel

10 The Diamond Reel / Miss Burnet of Monboddo’s Reel

11 Minuet (27) / Quick Step

12 Lady Betty Boyle’s Reel / Miss Scott’s Reel

13 Miss Bewment’s Minuet / Air (28)

14 Lady Betty Cochran’s Reel

15 Minuetto (7)

16 Lady Emelia Ker’s Minuet

17 Gavotta (29)

18 Miss Henderson’s Minuet / Lady Wallace’s Reel

19 Miss Pringle’s Reel

20 Miss Baird’s Minuet

21 Gavotta (22)

Solo

22 Allegro

23 Largo

24 Jigg

25 March

numbers in brackets refer to page numbers in the original 1783 print

*from Sixty eight New Reels Strathspeys and Quicksteps, 1793

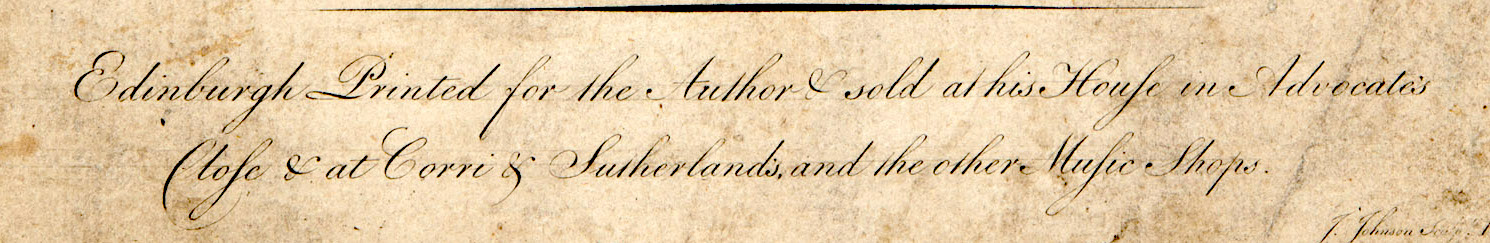

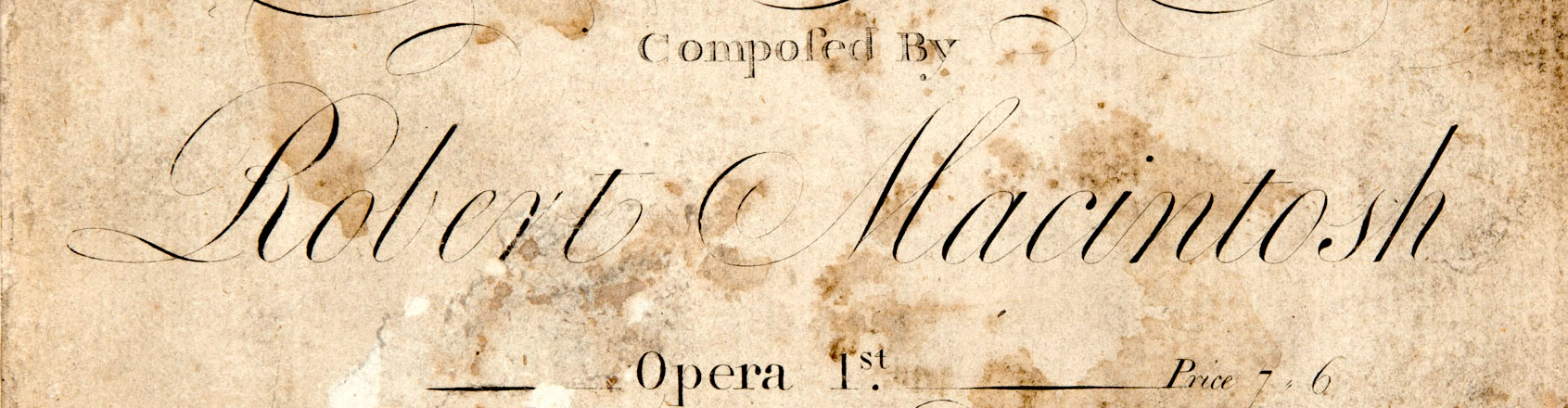

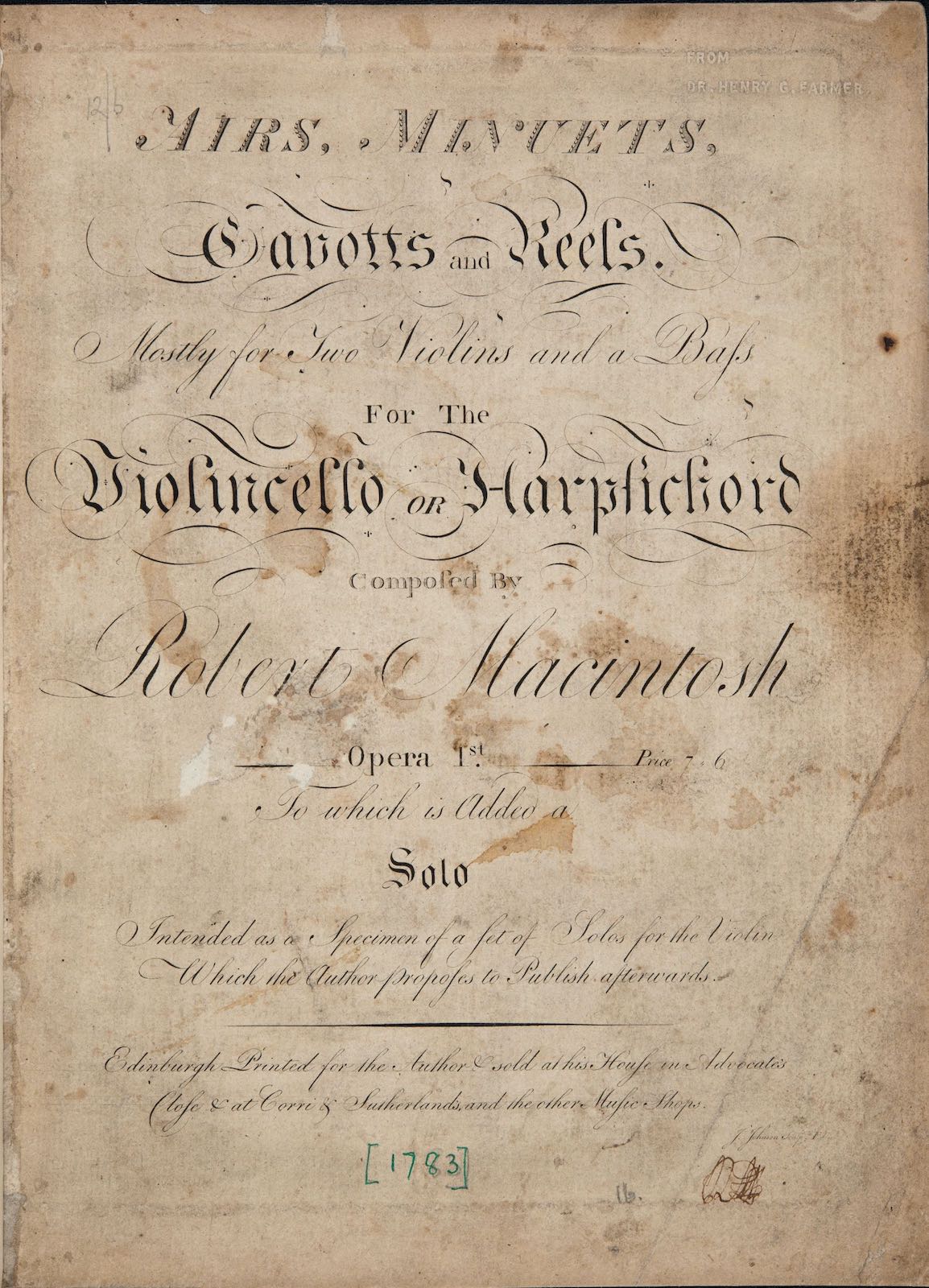

The late eighteenth century is sometimes described as the Golden Age of Scottish fiddle music. The church’s restrictions on country dancing were waning, Niel Gow and his son Nathaniel were each in their own way spectacularly successful, the publishing of fiddle music books was in full spate, and the familiar forms of strathspey, reel, and jig took their shape. But what did a dance band actually sound like? Then as now, there is no single answer, as to a large extent this music had not yet become ‘traditional’; much of it was still new, and it took quite different forms in the hands of the various musicians who were developing it. Airs, Minuets, Gavotts and Reels of 1783 was Robert Mackintosh’s first collection, and it represents his desire both to understand the musical world around him as fully as possible, and to forge himself a career within it. The title page tells its own rather eloquent story, which we’ll explore starting at the bottom of the page and working upwards.

Edinburgh. Printed for the Author & sold at his House in Advocate’s Close & at Corri & Sutherlands, and the other Music Shops

Mackintosh was born in Tulliemet in Perthshire, very close to the Gows’ home village of Inver. His birth date is uncertain, but most probably in the mid 1740s, which would put him between the father Niel and son Nathaniel in age. He would most likely have known Niel, and perhaps encountered a young Nathaniel, before leaving Perthshire for Edinburgh, where he is first recorded as living in 1773. The first of his thirteen children by his wife Margaret Mill was born in 1767, so they may have already been settled in Edinburgh by that time.

Red Rob, named in the customary Gaelic fashion after his hair, found himself a place in the orchestra of the Edinburgh Musical Society and set up business as a teacher. Besides the usual private lessons for gentlemen, he advertised a public violin class, ‘where any boy of ordinary genius, by devoting to this agreeable exercise some portion of the time destined to amusement, may soon acquire taste in music’. Group lessons were commonplace for voice or harpsichord, but were still a novel idea for the violin, and it may have been at these that Nathaniel Gow came to be his student.

As David Johnson has shown, Mackintosh was most likely the editor of Charles McLean’s A Collection of Favourite Scots Tunes of around 1773-4, composing some of the variation sets himself and adapting others. His growing family and the resulting financial pressures may have partly accounted for his restlessness, as he moved house within Edinburgh many times, and in 1779 complained to the Society about the level of his orchestral salary, just two years after they had discussed amongst themselves whether they really required his services at all. He probably presented his own concerts annually: in 1783 a concert of his featured no less a figure than Haydn’s collaborator, the violinist and impresario J. P. Salomon, who had only arrived in London two years previously. This suggests that Mackintosh was already making useful connections south of the border, and taking the trouble to stay in touch with the latest musical developments.

His singling out of Corri & Sutherland’s newly-opened shop on North Bridge Street may be an indication that Mackintosh saw himself too as a new kid on the block: this was only the fourth music shop to open in Edinburgh, but within 20 years there would be twelve, as the music trade grew rapidly and drifted across to the New Town along with the burgeoning middle classes.

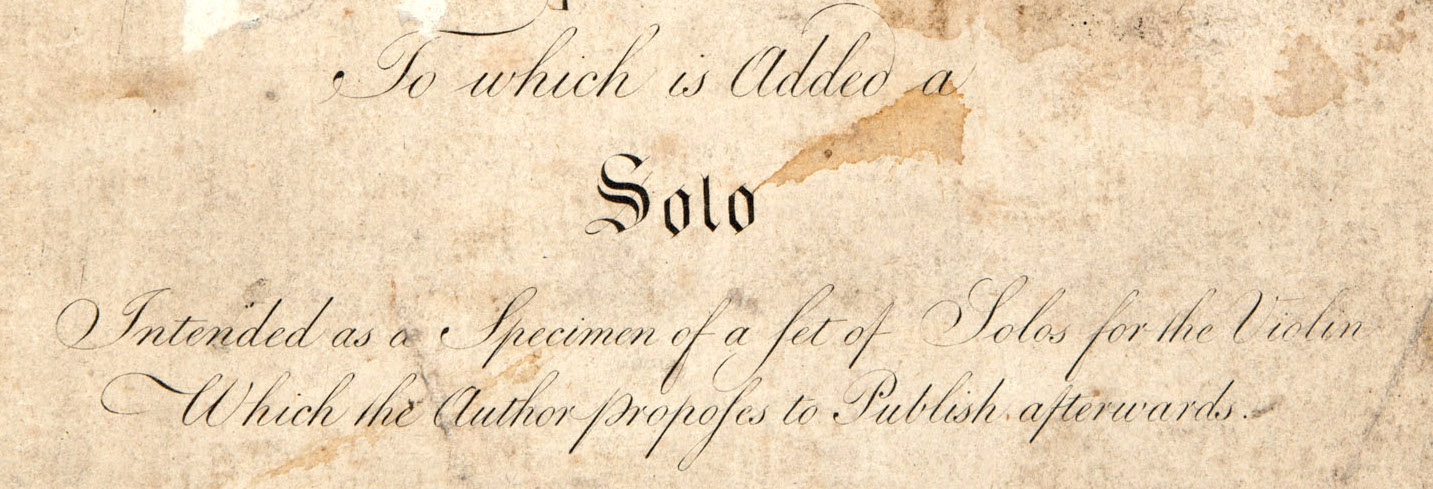

To which is Added a Solo Intended as a Specimen of a set of Solos for the Violin Which the Author proposes to Publish afterwards

At the back of the book Mackintosh establishes his credentials both as a concert artist and as a composer, with his three-movement ‘Solo’. The promised set of solos never materialised, and neither has his violin concerto survived which he performed in Aberdeen in 1786. Whether this is a measure of his lack of success as a soloist it is hard to say, but it is likely that a piece of such technical difficulty as this would have fallen on stony ground in Edinburgh at the time. A similar lack of local virtuosi prompted George Thomson to plead with Beethoven in 1812 to write simpler arrangements of Scottish airs that would be suitable for his customers.

The ‘Solo’ itself is a powerful expression of one aspect of Mackintosh’s musical personality, that of the concert virtuoso. David Greenberg describes the muscular first movement as ‘Boccherini on steroids’, a modish style which is all the more remarkable for the other two movements being in a musical language of a hundred years earlier, apart from their decadent and occasionally daring harmony. Mackintosh may have been setting himself up for his move to Aberdeen, where the regulations of the Musical Society decreed that the now old-fashioned music of Corelli would be played during each act of every performance, although in practice this rule was usually waived.

In 1784 the Aberdeen Musical Society was looking out for a leader ‘of second-rate abilities at least’ for its orchestra, most of which was made up of amateur gentlemen, with professionals engaged only as principals. After a season led by the Italian Alexander Dasti, they took the unusual step of employing a Scot in Red Rob, a daring experiment that their Edinburgh counterparts would never have risked. Sadly, the appointment was not a great success. Violin pupils were much less plentiful than in Edinburgh, so Mackintosh was once more struggling financially, and he had a very public row with the Society’s keyboard player John Ross about the proceeds from their respective benefit concerts. This led to his censure for behaviour which was ‘highly improper, reprehensible, and also indecent to the Company, it having happened on a Publick Concert Night’. His request for a second benefit concert of his own in the season was declined, and to make matters worse, the gentlemen of the orchestra voted against keeping him on as leader. However, after a brief return to Edinburgh at the end of 1788, he was back in Aberdeen for a couple of seasons at a reduced salary, as the second violin to the new leader, the Londoner Mr Thurstans.

By this time Mackintosh’s son Abraham was becoming successful in the family business, publishing his own first book Thirty New Strathspey Reels in 1792 before he moved to Newcastle five years later. Red Rob himself eventually left Edinburgh in 1803 for London, where his final collection was published, and where he died in 1807.

Composed by Robert Macintosh

Opera 1st Price 7/6

Red Rob clearly marks this book as his Opus 1, and only adopted the ‘k’ in the spelling of his surname from his second book onwards. The sale price represents over a week’s wages for a skilled worker, and was also the sum the best of the capital’s fiddlers might have earned for several hours’ playing at a ball in the Assembly Rooms. However, out of town the gig rate was considerably less, so this was not a book that a working musician would casually add to their library: it was aimed primarily at amateurs with a higher disposable income. What the professional musician could do is pay another musician who had invested in the book to copy parts of it out for him, as reliable music copying was one of the many skills in their armoury. By the publication of his third book in 1796 Mackintosh had got wise to this potential loss of income, and had prices printed on individual pages so that they could be sold separately for fourpence or eightpence each.

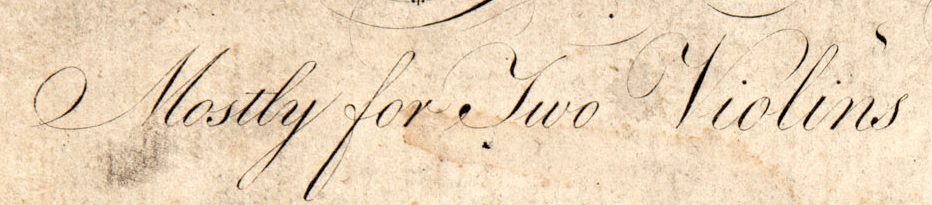

Mostly for Two Violins …

This claim is not strictly true, as only 23 out of the 52 items in the book have two violin parts. While it may be tempting to assume that the presence of two violin parts following (more or less) the rules of European harmony implies that the pieces concerned are what some commentators have called ‘drawing-room’ music, this would be misleading. It was not unusual for a fiddle band to have ‘firsts’ and ‘seconds’ (if usually only one of each), and while two violins and a bass was a standard baroque trio sonata line-up, it also made up a standard medium-sized Scottish dance band. The second violin and the cello were both to some extent optional, and could be dropped for lack of money or for lack of space, but having two violins and a bass was certainly a popular choice, and would allow for the playing of a wide variety of dances. John Morison of Peterhead, who published his own fiddle collections, advertised in 1805 that among his other musical services, ‘He also plays the Violin to Balls and Assemblies, and other public Dances, and takes with him an accompanying Violin and Violoncello, when desired.’

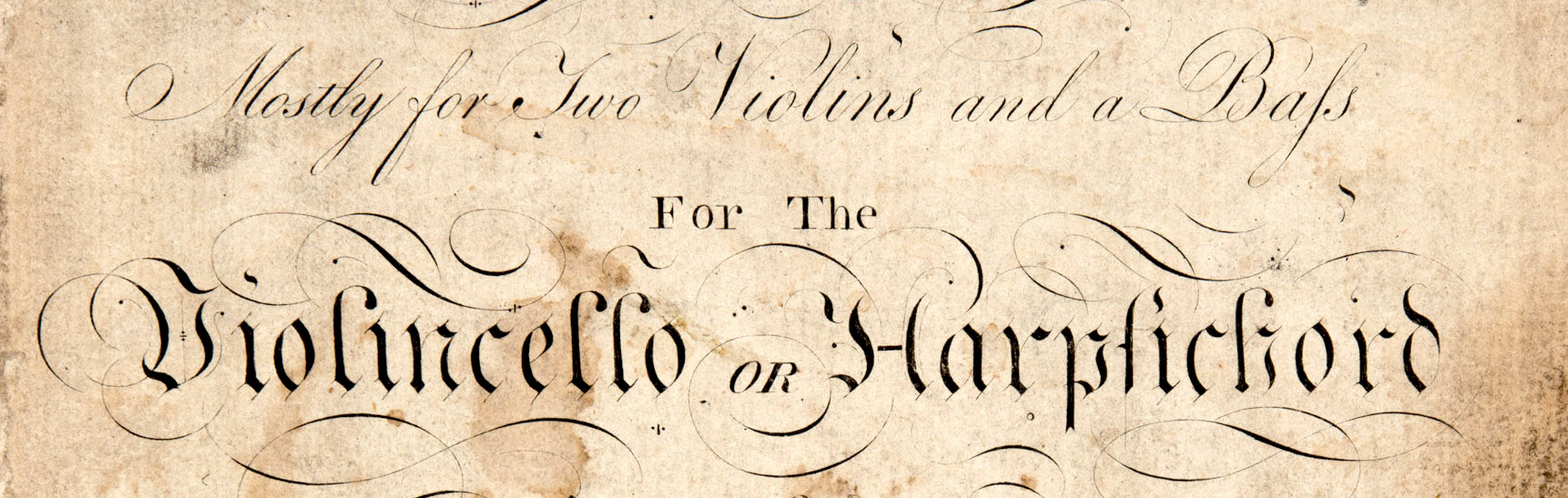

… and a Bass For The Violincello or Harpsichord

The ‘or’ here is probably inherited from the title of Corelli’s Opus 5 collection Sonate a violino e violone o cimbalo (Rome, 1700), a book that was familiar to all of Edinburgh’s professional violinists, and one that Niel Gow possessed and played from: his favourite movement according to Nathaniel was the Giga from the ninth sonata. By specifying either a bowed string instrument or a harpsichord, Corelli asked for only one instrument to accompany a solo performer, and unless the designation is a purely conventional one, Mackintosh expects the same in his music for two violins.

In part, the distinction between the use of cello and harpsichord is one of genre, as Mackintosh’s reels have bass lines which make little musical sense played on the harpsichord. However, the rest of the repertoire in the book is readily interchangeable between the two instruments, which suggests that the distinction is more one of environment. Cellos were far more mobile than harpsichords, so the music could be played with cello in a variety of social settings, from a cottage fireside or a village dance to the grandest ball in the Assembly Rooms. Performance with harpsichord was likely to be limited to wealthier houses, or a well-appointed public venue such as St Cecilia’s Hall.

Edinburgh music shops began to keep pianos as stock items from 1784: these were most probably squares rather than grands, as there had been only one grand piano in Scotland when Domenico Corri played a concerto at St Cecilia’s in 1776. But the piano’s supremacy had taken hold by 1790, so that when Mackintosh published his second book in 1793, the inclusion of ‘some slow Pieces with variations for the Violin and Piano Forte’ took precedence on the title page over the ‘Bass for the Violoncello or Harpsichord’.

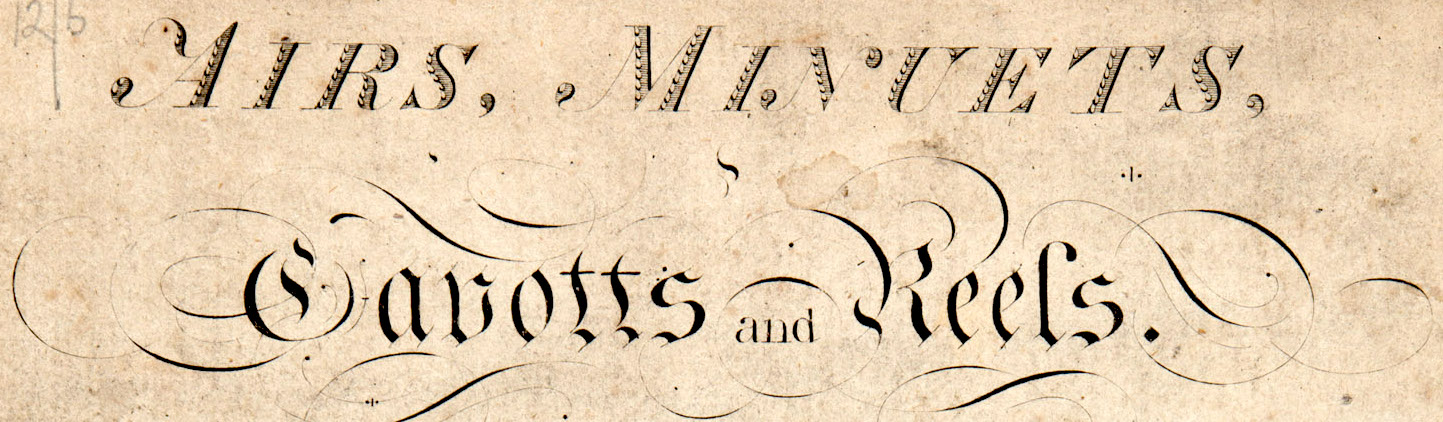

Airs, Minuets, Gavotts and Reels

The ordering of Mackintosh’s description of the book’s contents is unexpected, in that there are only five pieces in the book entitled ‘Air’, one of them a substantial set of fiddle variations. By contrast there are seventeen minuets.

There is evidence that some of Mackintosh’s minuets were sufficiently popular to be circulating in manuscript before publication, and that they continued to do so afterwards. Minuets had found their way into the Scottish fiddle tradition around the middle of the eighteenth century, as dancing masters across Scotland encouraged them to be danced on country greens as well as in urban ballrooms. James Oswald’s first publishing venture when he arrived in Edinburgh from Fife in the 1730s had been a book of minuets, and Neil Stewart found a ready market for his cheap and cheerful book of minuets from about 1770 onwards.

Mackintosh’s minuets show a great variety of structure in their length and presentation. Twelve of them are given two violin parts, five have contrasting minore or maggiore sections, and several others are paired with another dance that follows on afterwards, often a gavotte, but sometimes a jig, quickstep or reel. The two minuets which incorporate a set of variations are both in the key of E flat, a familiar enough key for minuets but unusually remote for the improvising of fiddle sets. The eight ‘Gavotts’ or ‘Gavottas’ display similar variety in their treatment and include two variation sets: the first of these is included on our album The Red Red Rose.

All but one of the seventeen reels appear in a long sequence just before the ‘Solo’ towards the end of the book. The terminology of ‘reel’ and ‘strathspey’ was still in the process of becoming standardised: to some, a ‘Strathspey reel’ was differentiated in character from an ‘Atholl reel’, but it was also accepted that the same tune could often be played in both styles. Mackintosh includes no unequivocal strathspeys until his second book, but one of the reels included in 1783 does feature the characteristic back-dotted rhythm of a strathspey, and the inclusion of dotted figures in many of the tunes suggests that the clear distinction between reels and strathspeys was still in the process of development.

The dedications of the reels and minuets almost entirely to young upper-class girls was an efficient way to cement relationships with musical patrons and to ensure healthy book sales. From 1793 onwards, Mackintosh was also to use the companion technique of a list of subscribers who paid upfront to have their names in print before publication.

The one remaining piece is the March which appears as a postscript at the very back of the book. This signing-off may suggest Mackintosh’s personal association with a military band, in the same way that the masonic anthems printed at the end of Oswald’s A Curious Collection of Scots Tunes would have had particular significance for only a selection of the book’s users.

The recording

The contents of the book prompt a number of questions about how to perform and record from it. One principle that we considered vital for the result to be meaningful as a representation of Mackintosh’s musical personality was that it should be demonstrably the same musicians playing all of the diverse repertoire. We resisted the temptation to follow the usual ‘early music’ habit of recording in a luxuriously resonant acoustic, as there is no evidence to suggest that Mackintosh’s music was generally performed in one.

As the piano made its impact on Edinburgh almost immediately after the book’s publication, we have included an Edinburgh-built square piano in some pieces, and featured it in a set of variations with violin accompaniment from Mackintosh’s 1793 book Sixty eight New Reels Strathspeys and Quicksteps. For the most part we kept to the ‘cello or harpsichord’ principle with the bass, only using the instruments together occasionally, and in one minuet (track 2) we employed the piano as a continuo instrument.

The bass lines for the reels are quite distinct in character from the rest of the material, and give a fairly sophisticated representation of dance band ‘bass fiddle’ cello practice, in contrast to the Italianate baroque style that features in Edinburgh publications of 40 years earlier. These basses are quite ineffective on the harpsichord, but it is possible that Red Rob might have encouraged a young lady to try them on the piano and provided fiddle accompaniment himself, as in ‘Miss Campbell’s Reel’. For ‘The Diamond Reel’ the piano and violin swap roles, and the piano accompanies the fiddle from Mackintosh’s bass line. Rather than assemble our own sets from Mackintosh’s reels, we have only constructed sets by playing tunes in the order in which they appear in the book.

We have preserved some other aspects of the book’s ordering, while still aiming to provide a coherent listening sequence. ‘Miss Grace Stewart’s Minuet’ is followed by its Gavotta, ‘Miss Henderson’s Minuet’ and ‘Lady Wallace’s Reel’ are a pair, ‘Lady Emelia Ker’s Minuet’ has its variations and related jig, a practice already becoming outdated by the 1780s, ‘Miss Bewment’s Minuet’ has a following Air, and we play the Minuet and Quickstep (track 11) in the manner of a minuet and trio, with a da capo repeat of the minuet. We moved the Gavott from its place after ‘Miss Bewment’s Air’ and gave it to Lady Emelia Ker, and similarly borrowed Lady Marry Ann Carnegie’s Gavotta to follow ‘Miss Baird’s Minuet’. We gave ‘Miss Grace Stewart’s Minuet’ to the cello, as a nod to the Hungarian cellist J. G. Christoph Schetky who played alongside Robert Mackintosh in the Edinburgh Musical Society’s orchestra.

David Johnson suggested that Mackintosh was ‘a composer who missed greatness by a small margin’, which seems rather generous to Rob’s compositional ambition and technique, in classical terms at least. Perhaps if his violin concerto had survived, or even his ‘Solo in the manner of a Rondo, with harmonic Tones’, we might have reason to think differently. However, as a brilliant and powerful musical personality who shaped the music around him after his own likeness, bringing character and imagination to his work in all of its diversity, his achievements are considerable.

In a later era, James Scott Skinner, another unashamed concert virtuoso within the Scottish fiddle tradition, took a sideswipe at the Golden Age’s lack of technical accomplishment in performance, and included Mackintosh among the ‘natural geniuses’ and ‘immortals’ in his criticism: ‘All these men did good work, but would have soared even higher had they received a good sound training in manual equipment.’ Clearly Scott Skinner knew Red Rob’s reels and strathspeys, but not his ‘Solo’, nor the rest of his remarkable Airs, Minuets, Gavotts and Reels.

© 2013 David McGuinness

Images from Henry Farmer’s copy in University of Glasgow Library Archives and Special Collections – Mackintosh signed it with his initials ‘RM’ at the bottom of the titlepage

![]() I am horrified to realise how little I know of Scotland's music. And here is a revelation, thanks to that Indiana Jones of Scottish music, David McGuinness, and his piratical band, Concerto Caledonia. Robert Mackintosh, known as "Red Rob", was a Perthshire musician, born in 1745, and clearly a man with an enquiring mind and a broad palate. His fascinating history, which took him all over Scotland and down south, is recounted in detail in the liner notes for this irresistible CD, which features the music of his first published set of pieces, an enthralling collection in both classical and what we now call traditional styles. Reels nestle foot-tappingly alongside gavottes (spelled here with no "e") and minuets, all traditional classical forms, but with a twang, and there is a wonderful so-called Solo, in effect a three-movement solo sonata. The playing is exhilarating, and wait until you hear McGuinness going mental on the square piano. Brilliant – and important – stuff.

I am horrified to realise how little I know of Scotland's music. And here is a revelation, thanks to that Indiana Jones of Scottish music, David McGuinness, and his piratical band, Concerto Caledonia. Robert Mackintosh, known as "Red Rob", was a Perthshire musician, born in 1745, and clearly a man with an enquiring mind and a broad palate. His fascinating history, which took him all over Scotland and down south, is recounted in detail in the liner notes for this irresistible CD, which features the music of his first published set of pieces, an enthralling collection in both classical and what we now call traditional styles. Reels nestle foot-tappingly alongside gavottes (spelled here with no "e") and minuets, all traditional classical forms, but with a twang, and there is a wonderful so-called Solo, in effect a three-movement solo sonata. The playing is exhilarating, and wait until you hear McGuinness going mental on the square piano. Brilliant – and important – stuff.![]()

Michael Tumelty, Sunday Herald 7 April 2013

![]() Robert Mackintosh, known as "Red Rob", was born in the 1740s and died in 1807, having spent most of his life as a violin teacher and composer in Edinburgh and Aberdeen. Intensive googling didn’t supply me with much more in the way of biographical info, but a few minutes in the company of Mackintosh’s music leads you to speculate that he’d have made convivial, lively company. This is life-enhancing stuff – a disc guaranteed to put a spring into the heaviest, most jaded of steps. Mackintosh’s adherence to fairly standard musical forms doesn’t restrict his imagination, and the sequence of dances on this recording teem with life. He was never “a composer who missed greatness by a small margin” as one writer suggested, but a highly entertaining minor talent.

Robert Mackintosh, known as "Red Rob", was born in the 1740s and died in 1807, having spent most of his life as a violin teacher and composer in Edinburgh and Aberdeen. Intensive googling didn’t supply me with much more in the way of biographical info, but a few minutes in the company of Mackintosh’s music leads you to speculate that he’d have made convivial, lively company. This is life-enhancing stuff – a disc guaranteed to put a spring into the heaviest, most jaded of steps. Mackintosh’s adherence to fairly standard musical forms doesn’t restrict his imagination, and the sequence of dances on this recording teem with life. He was never “a composer who missed greatness by a small margin” as one writer suggested, but a highly entertaining minor talent.

The pieces here are all taken from Mackintosh’s first collection of violin pieces, published in 1783. Some are duets, and they’re all pleasingly accompanied, variously, by cello, harpsichord and a nicely rattly square piano. Several of the minuets feel a little strained, but the reels are effervescent. An extended three movement solo finishes with a witty jig. Close your eyes and you’re transported back in time. Idiomatic, affectionate performances from a downsized Concerto Caledonia. Delicious.![]()

theartsdesk.com 6 April 2013

![]() Record shop proprietors – such as are left in these uncertain times – will be scratching their heads yet again as to exactly which rack in which to place the latest recording from Scottish early music champions Concerto Caledonia: “Folk, classical... or what?”

Record shop proprietors – such as are left in these uncertain times – will be scratching their heads yet again as to exactly which rack in which to place the latest recording from Scottish early music champions Concerto Caledonia: “Folk, classical... or what?”

Featuring David Greenberg and Greg Lawson on violins, Alison McGillivray on cello and director David McGuinness on harpsichord and piano, Robert Mackintosh: Airs, Minuets, Gavotts and Reels (Delphian) delivers exactly what it says on the tin, celebrating the music of the Perthshire-born fiddler and composer “Red Rob” Mackintosh, a product of the 18th-century “golden age of Scots fiddling”, whose reputation hasn’t worn quite as well as his near contemporaries Niel and Nathaniel Gow or William Marshall.

Born around 1745, Mackintosh, like his contemporaries, played and composed “folk” and “art” music without any great distinction, except perhaps in the venues in which they were performed – dance assembly, drawing room or that newfangled concept, the concert hall. The album is drawn almost entirely from Macintosh’s first published collection, Airs, Minuets, Gavotts and Reels – the kind of repertoire, says McGuinness, that suggests an all-round musician showing what he can do, although in fact Mackintosh’s “classical” material has tended to fall by the wayside, while it is his brisk reels that tend to be played today.

Unlike some of this adventurous early music outfit’s more eclectic projects, the players lift the composer’s work faithfully off the page, to render it in the style in which it would have been delivered, taking the advice of Mackintosh’s title page and accompanying the tunes with either cello or harpsichord, while occasional use is made of a square piano built in Edinburgh around 1815, as a nod to the fact that the piano started to make its presence felt in music-making in the city shortly after the book’s publication in 1783.

McGuinness gives that venerable instrument the time of its life in The Duchess of Gordon’s Delight, the one track taken from Mackintosh’s second collection.

Listen to McGillivray’s wonderfully springy cello accompaniment louping along under Greenberg and Lawson’s animated fiddling in tunes such as Lady Betty Boyle’s Reel, and you’re hearing the kind of “bass fiddle” accompaniment that would have powered dance bands in Edinburgh’s Assembly rooms during the later 18th century, Mackintosh’s virtuosic showpiece is the more baroque-sounding three-movement Solo (which in fact features a busy harpsichord continuo), its introductory movement described by fiddler Greenberg as “Boccherini on steroids”. There is, says McGuinness, “a wonderful angularity about Mackintosh’s tunes. They whizz about the fiddle in quite a characteristic and unusual way.”

That whole bass question is currently a preoccupation for McGuinness, owing to his involvement in Bass Culture, a three-year project involving Glasgow and Cambridge universities and the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, which is challenging conventional thinking on the melodic basis of British and European folk music, and tracing the evolving nature and importance of bass accompaniment.

The album’s sleeve notes provide insight into the sometimes hand-to-mouth life of a professional musician of the day. That first tune collection of Mackintosh’s sold at 7/6d, which, in 1783, as McGuinness points out, “represents over a week’s wages for a skilled worker, and was also the sum the best of the capital’s fiddlers might have earned for several hours’ playing at a ball in the Assembly Rooms. However, out of town the gig rate was considerably less, so this was not a book that a working musician would casually add to their library; it was aimed primarily at amateurs with a higher disposable income.”

In Mackintosh’s case, the need to earn a living took him between Aberdeen and Edinburgh. Ultimately, the fiery haired and, by all accounts, abrasively tempered “Red Rob” went to London, where he died in 1807. The burying place of the man who produced such enduringly spirited music is not known.![]()

Jim Gilchrist, The Scotsman 4 April 2013