Mungrel Stuff

Scottish-Italian and Italian-Scottish music by Barsanti and others

with

Mhairi Lawson, soprano Jamie MacDougall, tenor

Chris Norman, flute & whistle Adrian Chandler, violin

Sunday Times Records of the Year 2001:

"Everything is infectiously played and sung.

Bizarre, but utterly compelling."

Mungrel Stuff

Scottish-Italian music by Francesco Barsanti & others

Concerto Caledonia

directed by David McGuinness

Mhairi Lawson, soprano

Jamie MacDougall, tenor

Chris Norman, flute & whistle

Elisabeth Dooner, flute

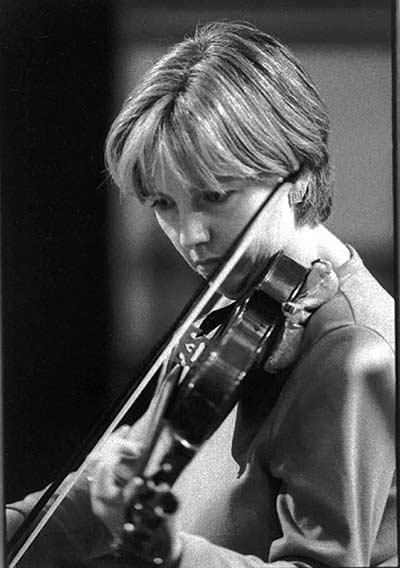

Lucy Russell, Adrian Chandler, Joanna Parker, Sarah Bevan-Baker, violins

Katherine McGillivray, viola

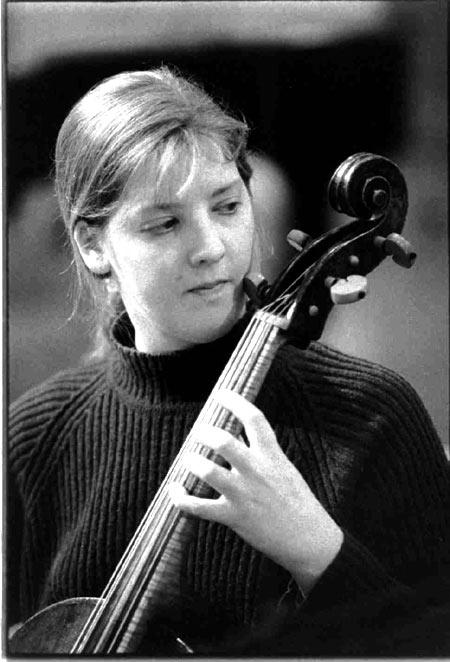

Alison McGillivray, cello

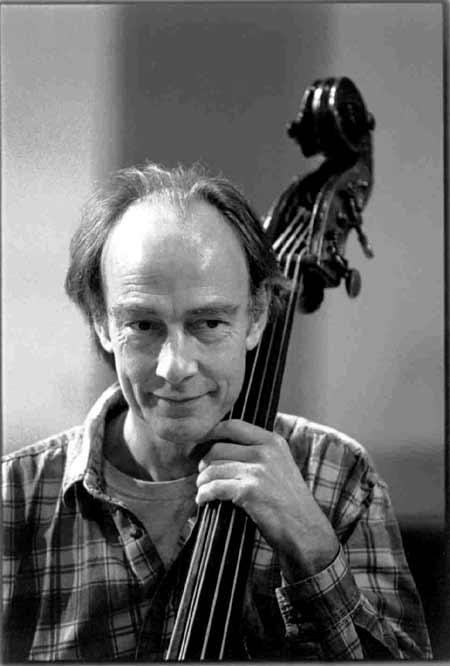

Ninian Perry, double bass

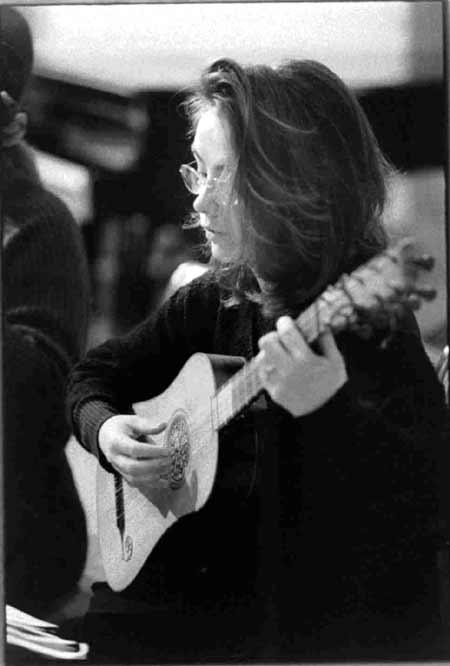

Elizabeth Kenny, guitar & theorbo

Steve Player, guitar

David McGuinness, harpsichord

Produced by David McGuinness and Philip Hobbs.

Recorded and mixed by Calum Malcolm.

Edited by David McGuinness.

Mastered by Ben Turner at Finesplice.

Recorded in Edinburgh, 26 October 1999, 20 & 23 January 2000 in BBC Studio 1, and 30 March 2001 in St Cecilia’s Hall.

Harpsichord by John Broadwood 1793, courtesy of the Russell Collection, University of Edinburgh, prepared and tuned by John Raymond (tracks 11 & 19).

Cover illustration by Joseph Davie.

Thanks to everyone who took part, and barks of appreciation to these kind souls, who influenced the end result for good in various ways:

Calum Malcolm and Lynda Cochrane for production assistance; Iain McGillivray for practical help and fabulous genes; Billy Kelly; Davitt Moroney and Olivier Baumont; the staff of the National Library of Scotland, Glasgow University Library, and the Mitchell Library, Glasgow; Helen Jamieson and the music committee of the Scottish Arts Council; Sandrine Pasquier; James Donegan and the Anniesland Occasionals; Ursula Leveaux; Noel O’Regan; Rebecca Tavener; Grant O’Brien; Tony Kime; the entire staff of MAD Enterprises and the inhabitants of the LA idyll - woof, DMcG

1

Corn Riggs Are Bonny

Francesco Barsanti (1690-1772)

ML CN JP SBB KMcG AMcG NP SP DMcG

2

She Raise and Loot Me In

Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762)

JMacD CN ED JP SBB KMcG AMcG NP EK DMcG

3

Sonata in imitation of Corelli

Adagio / Allegro / Largo / Allegro

William McGibbon (1696-1756)

LR SBB AMcG DMcG

4

Tweed Side

William Thomson (c.1684-c.1760); James Oswald (1710-69)

JMacD CN SBB AMcG NP EK DMcG

5-6

Sonata in A op. 2 no. 9

Francesco Maria Veracini (1690-1768)

5 Allegro moderatamente

6 Adagio / Scozzese: un poco andante et affettuoso

AC AMcG EK DMcG

7-10

A Scots Cantata

Lorenzo Bocchi (fl. 1720)

7 Recitative: Blate Jonny faintly teld fair Jean his mind

8 Air - spiritoso: O bonny lassie

9 Recitative: These tender notes did a’ her pity move

10 Air - allegro: Hence frae my breast, contentious care

ML LR SBB AMCG EK DMcG

11

Duncan Gray

Domenico Corri (1744-1825)

DMcG

12

Gilderoy / The Highland Laddie / Clout the Caldron

Francesco Barsanti (1690-1772)

JMacD CN JP SBB KMcG AMcG NP EK DMcG

13

Johnnie Faa

Francesco Barsanti (1690-1772)

CN KMcG AMcG NP SP DMcG

14

Bessy Bell and Mary Gray

Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762)

JMacD CN EK JP SBB KMcG AMcG NP EK DMcG

15

Lord Aboyne’s Welcome or Cumbernauld House

Francesco Barsanti (1690-1772)

CN AMcG SP DMcG

16

Pinky House

James Oswald (1710-69)

ML LR SBB KMcG AMcG NP SP DMcG

17

Hamilton House

James Oswald (1710-69)

CN JP SBB KMcG AMcG NP SP DMcG

18

Leader Haughs and Yarrow

Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762)

JMacD CN ED JP SBB KMcG AMcG NP EK DMcG

19

Steer Her Up and Had Her Gawn

Alexander Reinagle (c.1750-1809)

DMcG

20

The Lass of Peaty’s Mill

Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762)

JMacD CN ED JP SBB KMcG AMcG NP EK DMcG

Then you whose Symphony of Souls proclaim

Your Kin to Heav'n, add to your Country's Fame,

And shew that Musick may have as good Fate

In Albion's Glens, as Umbria's green Retreat :

And with Correlli's soft Italian Song

Mix Cowdon Knows, and Winter Nights are long.

In 1721, when Allan Ramsay wrote this address to the Musick Club in Edinburgh, he little knew just how much these wishes would come true. John Clerk of Penicuik, a Club member, had already familiarised himself with Corelli’s soft Italian song in Rome in the 1690s, and another Italian composer, Lorenzo Bocchi, had just arrived in Edinburgh. Over the coming decades, Bocchi would be followed by a succession of singers, musicians and composers from Italian green retreats - Barsanti, Corri, Pasquali, Stabilini, Urbani - and the musical fascination for all things Italianate was to continue in Scotland until the end of the eighteenth century.

Bocchi came to Edinburgh in 1720 with one Mr. Gordon, keen to establish a home for pastoral opera in Edinburgh, and his Scots Cantata to words by Ramsay is all that survives of his attempt. Ramsay was soon to have an enormous success with his own brand of pastoral opera, when at the request of Haddington Grammar School he added more songs to his verse drama The Gentle Shepherd, and in due course it became the biggest Scottish stage hit of the century. But in The Gentle Shepherd the music was resolutely Scots: perhaps Bocchi’s rumbustious setting of Johnny’s plaintive moan put Ramsay off any further Italian experiments.

Francesco Barsanti’s eight years in Edinburgh from 1735 were certainly fruitful: he married a Scots lass, and he published an excellent set of twelve concerti grossi in 1742. But this has overshadowed another little book he produced in the same year, of Old Scots Tunes. The similarity of some of Barsanti’s basslines to those in Oswald’s Sonata of Scots Tunes (on our album Colin’s Kisses) suggests that they may have collaborated, if not borrowed from one another’s work. Oswald had left Edinburgh two years previously, but I won’t dare to speculate on who did the ‘borrowing’. The tunes in Barsanti’s book are heavily ornamented, which at first sight looks like the ‘Italianising’ that native musicians later in the century came to deplore. But on closer examination this looks like a serious musical attempt to notate the tunes as he heard them played, rather like Percy Grainger’s meticulous writing-down of the twiddly bits when he collected folk songs two centuries later.

The best of Barsanti’s basslines lend themselves to serious session playing rather than polite chamber music, and in our versions we’ve used a combination of written down arrangements and improvisation. He was a flute and oboe player rather than a violinist, and his selection of tunes suit the flute particularly well. Keen musicologists may like to note that the opening basslines of Clout the Caldron and Johnnie Faa are virtually identical, and that Barsanti marked every tune in his collection ‘slow’: this advice we have chosen to ignore.

We added Ramsay’s words to Clout the Caldron and to Corn Riggs, which is the final number in The Gentle Shepherd, sung by Peggy after she is reunited with her sweetheart, the gentle shepherd Patie. The tune, which with Burns’s later words now seems so characteristically Scottish, actually began as a piece of fake London Scotchery written by Thomas Farmer in 1680 to the words ‘Sawney was tall’, for Tom D’Urfey’s comedy The Virtuous Wife.

In Clout the Caldron, a traveller tries to charm his way into a kitchenware maintenance job (and more besides), with a combination of subtle innuendo, and some rather incongruous appeals to classical precedent. He is of course sent packing. Burns used the same tune for his tinker’s song in The Jolly Beggars, and in our version the percussion sounds are the clouting of instruments, harpsichord and guitar being the loudest.

Johnnie Faa really is an Old Scots Tune: it appears in the Skene MS of the early 17th century as ‘Ladie Cassilles Lilt’. The ballad sung to it is The Gypsy Laddie, which tells of the Countess of Cassilis’ elopement with her lover, Sir John Fall, disguised as a gypsy. When they are caught and brought back to Cassilis House, she has to witness the hanging of the entire gypsy community, Johnnie Faa included. Gilderoy, or Gille Ruadh tells of another rogue who met a sticky end, the red-haired Patrick Macgregor, a robber of some repute in Perthshire in the 1630s.

Barsanti’s The Highland Laddie is not the well-known Jacobite song to the Canadian sea-chanty ‘Donkey-Riding’, nor is it quite the tune for the song that begins ‘the Lowland Lads think they are fine’, although it’s fairly similar. Oswald included this tune in his Curious Collection of Scots Tunes of 1740, but he called it The Highland Lassie.

Francesco Geminiani may well have visited Scotland – along with Handel he dominated much of London musical life in the first half of the eighteenth century, besides spending some time in Paris and Dublin. In the 1720s he was part of a Masonic musical society along with Barsanti, who published his own trio sonata arrangements of Geminiani’s violin sonatas.

Geminiani’s Scots song settings appeared in 1749 as illustrations of the art of refined musical ornamentation, in his Treatise of Good Taste in the Art of Musick. Four years later, William Hayes wrote:

of late, he hath taken great Pains … in dressing up Trifles; particularly the Scotch Songs: The most we are indebted to him on this Account, is, for putting good Basses to the original Tunes; for in Truth, all beyond this, is such mungrel Stuff, that, it is not probable, it will obtain that Degree of General Approbation, which he might expect.

The Treatise is really only a glorified table of ornaments, although harpsichordists have reason to be grateful for its detailed description of how to play extremely loudly, by the use of acciaccature. But the book’s preface begins with an extraordinary paragraph worth quoting here in full. In his musical Apotheoses, the French composer François Couperin had allowed only two composers onto the divine heights of Parnassus: Jean-Baptiste Lully and Arcangelo Corelli, the supreme representatives of the French and Italian musical worlds respectively. Geminiani admits Lully for his mastery of the perfect simple melody, but he shares his heavenward journey not with the great Italian violinist, but with the enigmatic figure of Mary Queen of Scots’ murdered secretary and rumoured lover …

Two Composers of Musick have appear’d in the World, who in their different Kinds of Melody, have rais’d my Admiration; namely David Rizzio and Gio. Baptista Lulli; of these which stands highest in Reputation, or deserves to stand highest, is none of my Business to pronounce: But when I consider, that Rizzio was foremost in point of Time, that till then Melody was intirely rude and barbarous, and that he found Means at once to civilize and inspire it with all the native Gallantry of the SCOTISH Nation, I am inclinable to give him the Preference.

Now just who is Geminiani lionising here? Riccio (or Rizzio) was hardly a famous composer, if indeed a composer at all, although by all accounts he won his way into Mary's favours partly by his musical skill. By 1749, however, his name had taken on a peculiar significance. William Thomson attributed several songs to him in the first edition of his songbook Orpheus Caledonius in 1725, and other publishers followed his lead, ascribing their more obscure, unattributable or just odd-sounding tunes to Signor Rizzio. James Oswald may well have started the trend: even before he left Scotland, he was already passing off his own tunes in Edinburgh as new-fangled Italian sicilianos, and as works of historical antiquity. In his farewell epistle to Oswald in 1741, Allan Ramsay asked:

When wilt thou teach our soft Aeidian fair,

To languish at a false Sicilian air;

Or when some tender tune compose again,

And cheat the town wi’ David Rizo’s name?

By the middle of the 18th century the mythology was wearing thin, but even then it must have been an attractive idea for Geminiani to suggest that the pinnacle of French music had been reached by Lully, an Italian by birth, and that the seeds of a Celtic musical culture had been sown by another. Had he known of the great tradition of McCrimmon pipers, he would no doubt have delighted in pointing out their ancestry in Cremona as well.

His arrangements are most certainly mongrel stuff, as the tunes nestle amongst the most ornate of string and flute writing, and Geminiani divided each verse in two with a short interlude in the manner of London’s theatre songs. He also misunderstood the double bar that conventionally separates each strain of the tunes, and turned it into a repeat, so that each half of each verse gets sung twice – a misunderstanding that we have corrected. But Geminiani knew what he was doing when creating musical atmosphere, and once we’ve abandoned any search for artistic racial purity (which is a very dangerous pursuit anyway), we can enjoy the curious coming together of musical cultures that he created. In any case, She raise and loot me in is another piece of bogus Scotchery, probably by D’Urfey and Farmer again. Ramsay carefully adapted the words to make them sound more convincingly Scottish, and he described it as ‘an old song’ in Tea-Table Miscellany either in ignorance or, more likely, to cover up its Sassenach origins.

The Lass of Peaty’s Mill is rightly one of Ramsay’s most famous lyrics, and Bessy Bell and Mary Gray is one of his most notorious, because in his rewriting of the original ballad, preserving only its first four lines, he completely obscured the tale behind it. Bessy Bell and Mary Gray, the daughters of wealthy families in Perthshire, built their bower to escape the horrors of the plague in the 1660s, but they nevertheless caught the infection from a young gentleman of Perth who visited them regularly bringing provisions. The rumour was that he was the lover of one, if not both of them. The original ballad goes on to tell of their peculiar burial arrangements, but in his lyric Ramsay steers clear of anything so morbid. Scottish music purists will no doubt be offended by Geminiani’s wonderful shoe-horning of the tune’s binary harmonic ground into something approaching standard baroque harmony.

Leader Haughs and Yarrow seems a strange choice of song for him to arrange, as its twelve verses, which describe the places, flora and fauna of the area around the River Tweed and Yarrow Water, would surely have meant little to his London audience. Maybe he just liked the tune.

Francesco Maria Veracini never visited Scotland as far as we know, but he appreciated enough of the London craze for Scots tunes to incorporate variations on the tune Tweed Side into one of his sonate accademiche. This rather forbidding title implies only that the pieces are for private concerts or ‘academies’ rather than for the church or the theatre. Veracini’s phenomenally successful career as a violin virtuoso took him from his native Florence to posts in St Mark’s, Venice, the London theatre and the court of Dresden, and his departure from Dresden is shrouded in some mystery. He jumped from a third-floor window either to escape from a potential murderer, or, as suggested by the composer Mattheson (always a rich source of unreliable anecdote), in a fit brought on by extreme devotion to music and alchemy. He certainly had confidence in his talent, declaring ‘there is one God, and one Veracini’. The tune of Ramsay’s The Lass of Peaty’s Mill found its way into his last London opera, Rosalinda, and soon after leaving there in 1745 he was shipwrecked in the English Channel, losing a number of scores in the process. But he clearly recovered the Tweed Side sonata, as five years later we hear of him playing it in the presence of the British Envoy in Veracini’s native Florence. Tweed Side was a popular tune for fiddle variations, and during his stay in Edinburgh in the 1750s, Nicolo Pasquali also wrote a cantata based on it, but this has not survived.

William Thomson sang as a boy soprano in one of Edinburgh’s first public concerts, on St Cecilia’s Day in 1703 or 1704. Soon after settling in London, he published his lavish collection Orpheus Caledonius, or a Collection of the Best Scotch Songs set to Musick, in 1725, with a list of well-heeled subscribers and a dedication to the Prince of Wales. The texts of many of the fifty songs were taken directly from Allan Ramsay’s Tea-Table Miscellany, much to Ramsay’s annoyance (‘he ought to have acquainted his Illustrious List of Subscribers, that most of the Songs were mine’), and the tunes were highly ornamented, presumably in the manner of Thomson’s own singing. For the second edition eight years later, he expanded the book to 100 songs, restored some simplicity to the tunes, and improved his basslines, some of which had been rather crude. The result became the source-book for every composer and musician in London keen to exploit the fashion for all things Scotch. Geminiani, in his arrangements, didn’t even bother to print the words for more than one verse of each song, as he could safely assume that the reader would have access to Thomson’s popular book as well.

In Edinburgh, Allan Ramsay sanctioned and sold his own music book as a companion to his Tea-Table Miscellany, with the tunes simply if rather clunkily arranged by Alexander Stewart. Each of its six volumes is dedicated to a noble lady, although only the first four of these patrons have aristocratic titles, so perhaps Ramsay was running out of high-born customers as the series progressed. The significance of the dedicatees, and indeed in the title of his book, is that the songs were collected together to be sung by young society ladies at table after dinner.

The Wanton wee Thing will rejoice,

When tented by a sparkling Eye,

The Spinnet tinkling with her Voice,

It lying on her lovely knee.

Our version of Tweed Side uses the arrangement from the second edition of Thomson’s book, except for the third verse and the playout which are by Oswald. Ramsay did write his own lyrics to the tune, but these words by Robert Crawford always remained the more popular.

Contemporary with Ramsay in Edinburgh was William McGibbon, who was probably born in Glasgow. He was sent to London to study with the violinist and composer William Corbett, who also took him on his travels to Italy, and when McGibbon returned he became a well-loved pillar of the Edinburgh musical establishment, leading the orchestra of the Edinburgh Musical Society for thirty years. He published an exceptionally good set of Scots tunes in three books, and his chamber music includes this neatly crafted miniature homage to Corelli, with another new-fangled Italian siciliano for its third movement. On McGibbon’s death in 1756, the poet Robert Fergusson wrote with an admirably blunt finality:

Macgibbon gane, a’ waes my heart:

The man in music maist expert,

Wha could sweet melody impart

And tune the reed

Wi’ sic a slee and pawky art,

But now he’s dead.

Domenico Corri’s time with the Edinburgh Musical Society was to come later – he arrived in Edinburgh from Rome in 1771, and his variations and tambourin on the song Duncan Gray are the fruit of a flowering of commercial music in the late 18th century which David Johnson memorably described as ‘a free fight … to see who could write the most effective trash’. Trash it probably is, but it’s certainly very effective – an Italian composer writing a French dance on a Scots tune.

Portraits of Corri’s family now hang in St Cecilia’s Hall, where he put on concerts for several years, and when he left Edinburgh for London, he went into business with the Bohemian composer Dussek, and became the Scottish agent for Broadwood’s harpsichords and pianos. So, recording Corri’s music in the concert hall he knew, on an instrument that he may well have sold, built by an exiled Scot, was particularly appropriate.

Made in 1793 when the piano had largely become the keyboard of choice, the Russell Collection’s magnificent harpsichord by John Broadwood was the very last one to come from his London workshop, and the only one signed by him alone. It has a bewildering array of large brass knobs that operate the registers, a lute stop, and a pedal-operated machine stop for automatic registration changes, which engages with a satisfying clunk, heard here in Duncan Gray before the 7th variation. To compete with the new pianos, it also has a Venetian swell that enables the sound to get gradually louder or softer. It’s like a wooden Venetian blind mounted horizontally above the strings, which is opened and closed by the action of another pedal. We know that patent harpsichords with similar gadgets to Broadwood’s were current in Scotland at the time, as they were advertised for sale in the Glasgow Mercury in 1787, and such instruments are perfect for dealing with Corri’s copious (and bizarre) dynamic markings.

The tune Pinky House has a perfectly serviceable if conventional set of words ‘By Pinky House oft let me walk’, so it’s a measure of how decadent the approach to Scots tunes had become in the London of the 1760s, that James Oswald chose to set a more melodramatic text, and arrange it for the Italianate combination of voice and trio-sonata group. His approach to Hamilton House some twenty years earlier is much more straightforward.

Finally, Alexander Reinagle has no obvious Italian connections but his life is such a brilliant expression of ‘Mungrel Stuff’ that it’s impossible to leave him out. His father, who may have served in the Hungarian army, was Edinburgh’s state trumpeter, and Alexander’s book of Scots Tunes was published in Glasgow in 1782, although it says ‘London’ on the title page. Reinagle was working in Glasgow largely as a harpsichord teacher, and on his subsequent European travels he befriended CPE Bach, before emigrating across the Atlantic, to become involved in the setting up of opera houses in Baltimore and Philadelphia. He gave piano lessons to George Washington’s adopted daughter, and his sonatas in the style of CPE Bach were the first real American piano music, but his most unusual achievement is perhaps that the Philadephia edition of his little book of Scots Tunes was the first secular music publication in America.

The appetite for Scottish music in the New World was well established. Already by 1730, a Dr Bannerman had written to Allan Ramsay concerning the success of his Tea-Table Miscellany across the Ocean.

Here thy soft Verse, made to a Scottish Air,

Are often sung by our Virginian Fair.

Camilla’s warbling Notes are heard no more,

But yield to Last Time I came o’er the Moor;

Hydapses and Rinaldo both give way

To Mary Scot, Tweed-side and Mary Gray.

For him at least, the Scots had the musical edge on the Italians.

© David McGuinness 2001

Sources

Barsanti – A Collection of Old Scots Tunes (Edinburgh, 1742)

Bocchi – A Musicall Entertainment for a Chamber (Edinburgh?, c.1726)

Corri – Duncan Gray with Variation by Sigr. Corri (Edinburgh, 1780s)

Geminiani – A Treatise of Good Taste in the Art of Musick (London, 1749)

McGibbon – Six Sonatas for two German Flutes or two Violins and a Bass (Edinburgh, 1734)

Oswald – A Collection of the Best old Scotch and English Songs (London, 1761)

Oswald – A Collection of Curious Scots Tunes (London, c.1742)

Reinagle – A Collection of The Most Favourite Scots Tunes (Glasgow, 1782)

Thomson - Orpheus Caledonius, 2nd edition (London, 1733)

Veracini – Sonate accademiche (London, 1744)

All lyrics from Allan Ramsay’s The Tea-Table Miscellany (Edinburgh, 1724-29) as found in Thomson, except A Scots Cantata, taken directly from Ramsay, and Pinky House, from Oswald

Tracks 1, 12, 13, 17: arrangements by David McGuinness

Track 3: edited by Kenneth Elliott (London, 1963)

additional notes (David McGuinness 2002)

Most classical CDs are recorded in a few days in one concentrated burst, but I wanted this one to be a bit different. Rather than having an overall plan in mind, I thought it would be fun to add a day onto our schedule whenever we had a big concert, and record some of our new repertoire the morning after we'd played it live. It didn't quite work out like that in practice, but it was worth a try. I hoped that some coherent plan would emerge after we'd started, and sure enough it ended up as a Scottish-Italian record.

Originally it was going to be a CD of all the music from Geminiani's book on Good Taste. We dropped all the instrumental music from that, because we thought that the Palladian Ensemble were going to record it (they didn't), and then the Barsanti material started to get interesting and it took over. So if the end product looks terribly well thought out, it wasn't really.

Corn Riggs are bonny

I really like this one. The 20 January session (with Steve Player on guitar) came about because Chris was in Scotland playing a gig with Alasdair Fraser - some ringing round of various band members resulted in the realisation that the only time most of us would be free at the same time in the next 9 months was a 3 hour window on 20 January, so that's when the session was. We got on the train in Glasgow, Chris asked me 'so how does this tune go David?' and by lunchtime Corn Riggs and a few other tunes were in the can, and everyone scattered to the four winds again. Chris just happened to have a whistle about his person to play in the last two choruses, and the reason the intonation is so, ahem, exciting, is that the whistle was pitched at A440 and we were all playing at A415, one semitone lower. So he just pulled the whistle joint out as far as it would go and got on with it.

The tapping sounds are my wedding ring on the side of the harpsichord. Well, actually this isn't quite true - I did it in the session (quite chuffed with myself at managing to play at the same time), and Philip Hobbs thought it sounded too off-mic and asked me not to. Listening back to the session tapes when we mixed them over a year later I thought it sounded great, so we dubbed it back on, with me tapping on the music desk of Calum Malcolm's Yamaha baby grand piano instead.

She raise and loot me in

Here Liz Kenny wins the 'Most Outrageous Guitar Fill of 1999' award before the fourth verse.

Veracini sonata

The first time I met Adrian, we were in a taxi and he said 'do you know the Veracini sonata on Tweedside?' A few weeks later we played it on a live radio broadcast and I said 'do you want to play it on the next record?'. So here it is. This session was a little fraught, as nothing would dissuade the security man at the BBC to extend his shift past the Greenwich pips at 6pm that afternoon, so we had about an hour to record this display of fiddle pyrotechnics, not having rehearsed it for 4 months. Sometimes a bit of fear and panic brings out the best in people - certainly in extrovert music like this.

Duncan Gray

Operating the pedals on the 1793 Broadwood is a bit like learning to drive: 'OK, left foot down, ease up on the right'. There's a note in the score which reads 'The 6th variation may be left out if it is too difficult for the performer': no chance.

A Scots Cantata

Yes, I know 'die' should rhyme with 'thee' - don't know what came over us that day to change it.

1

Corn Riggs are bonny

My Patie is a Lover gay,

His Mind is never muddy,

His Breath is sweeter than new Hay,

His Face is fair and ruddy.

His Shape is handsome, middle Size;

He’s stately in his wawking:

The shining of his Een surprise; [eyes

‘Tis Heaven to hear him tawking.

Last Night I met him on a Bawk, [ridge

Where yellow Corn was growing,

There mony a kindly Word he spake,

That set my Heart a glowing.

He kiss’d, and vow’d he wad be mine,

And loo’d me best of ony; [loved

That gars me like to sing sinsyne, [since then

O Corn Riggs are bonny.

Let Maidens of a silly Mind,

Refuse what maist they’re wanting,

Since we for yielding are design’d,

We chastly should be granting:

Then I’ll comply, and marry Pate,

And syne my Cockernony, [*

He’s free to touzle air or late, [early

Where Corn Riggs are bonny.

*The gathering of a Woman’s Hair, when ’tis wrapt or snooded up with a Band or Snood. (Ramsay)

2

She raise and loot me in

The Night her silent Sable wore,

And gloomy were the Skies;

Of glittering Stars appear'd no more

Than shone in Nelly's Eyes.

When at her Father's Yate I knock'd, [gate

Where I had often been,

She, shrowded only with her Smock,

Arose and loot me in.

Fast lock'd within her close Embrace,

She trembling stood asham'd;

Her swelling Breast and glowing Face,

And ev'ry Touch enflamed.

My eager Passion I obey'd,

Resolv'd the Fort to win;

And her fond Heart was soon betray'd,

To yield and let me in.

Then, then, beyond expressing,

Transporting was the Joy;

I knew no greater Blessing,

So blest a Man was I.

And she, all ravish'd with Delight,

Bid me oft come again;

And kindly vow'd, that ev'ry Night,

She'd rise and let me in.

But ah! at last she prov'd with Bairn,

And sighing sat and dull,

And I that was as much concern'd,

Look'd e'en just like a Fool.

Her lovely Eyes with Tears ran o'er,

Repenting her rash Sin:

She sigh'd, and curs'd the fatal Hour,

That e'er she loot me in.

But who cou'd cruelly deceive,

Or from such Beauty part:

I lov'd her so, I could not leave

The Charmer of my Heart;

But wedded, and conceal'd our Crime:

Thus all was well again;

And now she thanks the happy Time

That e'er she loot me in.

4

Tweed Side

What Beauties does Flora disclose?

How sweet are her Smiles upon Tweed?

Yet Mary's still sweeter than those;

Both Nature and Fancy exceed.

No Daisy, nor sweet blushing Rose,

Nor all the gay Flowers of the Field,

Nor Tweed gliding gently thro' those,

Such Beauty and Pleasure does yield.

The Warblers are heard in the Grove,

The Linnet, the Lark, and the Thrush,

The Black-bird, and sweet cooing Dove,

With Musick enchant ev'ry Bush.

Come, let us go forth to the Mead,

Let us see how the Primroses spring,

We'll lodge in some Village on Tweed,

And love while the feather'd Folks sing.

How does my Love pass the long Day?

Does Mary not 'tend a few Sheep?

Do they never carelessly stray,

While happily she lies asleep.

Tweed's Murmurs should lull her to rest;

Kind Nature indulging my Bliss,

To relieve the soft Pains of my Breast,

I'd steal an ambrosial Kiss.

'Tis she does the Virgins excell,

No Beauty with her may compare;

Love's Graces all round her do dwell,

She's fairest where thousands are fair.

Say, Charmer, where do thy Flocks stray?

Oh! tell me at Noon where they feed;

Shall I seek them on sweet winding Tay,

Or the pleasanter Banks of the Tweed?

7-10

A Scots Cantata

The tune after an Italian manner.

Compos’d by Signior Lorenzo Bocchi

7 Recitative

Blate Jonny faintly teld fair Jean his mind, [bashful

Jeany took Pleasure to deny him lang

He thought her Scorn came frae her Heart unkind,

Which gart him in Despair tune up this Sang. [made

8 Air

O bonny Lassie, since ‘tis sae,

That I’m despis’d by thee,

I hate to live; but O I’m wae,

And unko sweer to die. [strangely slow

Dear Jeany, think what dowy Hours [melancholy

I thole by your Disdain; [endure

Ah! should a Breast sae saft as yours

Contain a Heart of Stane.

9 Recitative

These tender Notes did a’ her Pity move,

With melting Heart she listned to the Boy;

O’ercome she smil’d, and promis’d him her Love:

He in Return thus sang his rising Joy.

10 Air

Hence frae my Breast, contentious Care,

Ye’ve tint the Power to pine; [lost

My Jeany’s good, my Jeany’s fair,

And a’ her Sweets are mine.

O spread thine Arms and gi’e me Fowth [abundance

Of dear enchanting Bliss,

A thousand Joys around thy Mouth

Gi’e Heaven with ilka Kiss. [every

12

Clout the Caldron

Have you any Pots or Pans,

Or any broken Chandlers?

I am a Tinkler to my Trade,

And newly come frae Flanders.

As scant of Siller as of Grace; [silver

Disbanded, we've a bad-run;

Gar tell the Lady of the Place,

I'm come to clout her Caldron. [mend (or hit)

Madam, if you have Wark for me,

I'll do't to your Contentment,

And dinna care a single Flie

For any Man's Resentment:

For, Lady Fair, tho' I appear,

To every ane a Tinkler;

Yet to yoursell I'm bauld to tell,

I am a gentle Jinker. [dodger

Love Jupiter into a Swan

Turn'd, for his lovely Leda;

He like a Bull o'er Meadows ran,

To carry aff Europa.

Then may not I, as well as he,

To cheat your Argos blinker,

And win your Love like mighty Jove,

Thus hide me in a Tinkler.

Sir, ye appear a cunning Man,

But this fine plot you'll fail in,

For there is neither Pot nor Pan

Of mine, you'll drive a Nail in.

Then bind your Budget on your Back, [stock

And Nails up in your Apron;

For I've a Tinkler under Tack, [hire

That's us'd to clout my Caldron.

14

Bessy Bell and Mary Gray

O Bessy Bell and Mary Gray,

They are twa bonny Lasses,

They bigg'd a Bower on yon Burn-brae, [built; hill above a stream

And theek'd it o'er wi' rashes. [thatched

Fair Bessy Bell I loo'd yestreen, [loved last night

And thought I ne'er cou'd alter;

But Mary Gray's twa pawky Een, [rougish eyes

They gar my Fancy falter. [make

Now Bessy's Hair's like a Lint-tap; [*

She smiles like a May morning,

When Phoebus starts frae Thetis' Lap,

The Hills with Rays adorning:

White is her Neck, saft is her Hand,

Her Waste and Feet's fu' genty; [handsome

With ilka Grace she can command; [every

Her Lips, O wow! they're dainty.

And Mary's Locks are like the Craw, [crow

Her Een like Diamonds glances;

She's ay sae clean, redd up and braw, [dressed up; fine

She kills whene'er she dances:

Blyth as a Kid, with Wit at will,

She blooming tight and tall is;

And guides her Airs sa gracefu' still,

O Jove! she's like thy Pallas.

Dear Bessy Bell and Mary Gray,

Ye unco fair oppress us; [very

Our Fancies jee between you twa [swither

Ye are sic bonny Lasses;

Wae's me! for baith I canna get,

To ane by Law we're stented; [stretched

Then I'll draw Cuts, and take my Fate, [straws

And be with ane contented.

* lint-tap: a bundle of dressed flax put on a distaff for spinning; describing very fair hair [from the Concise Scots Dictionary]

16

Pinky House

As Sylvia in a Forest lay,

To vent her Woes alone

Her Swain Sylvander came that way,

And heard her dying Moan.

Ah! Is my Love she said to you

So worthless and so vain?

Why is your wonted fondness now

Converted to disdain?

You vow’d the Light shou’d Darkness turn,

E’er you’d exchange your Love,

In Shades let now Creation mourn,

Sylvander faithless prove:

Was it for this I credit gave

To ev’ry Oath you swore?

But ah! I find they most deceive

Who most our Charms adore.

‘Tis plain your Drift was all Deceit,

The Practice of Mankind;

Alas I see it – but too late!

My Love has made me blind;

For you delighted I cou’d die,

But ah! With Grief I’m fill’d,

To think poor cred’lous constant I,

Should by your scorn be kill’d.

This said, all breathless sick and pale,

Her Head upon her Hand,

She found her vital Spirits fail,

Her Senses at a Stand;

Sylvander now begins to melt

But e’er the Word was giv’n

The heavy Hand of Death she felt

And sigh’d her Soul to Heav’n.

[one verse omitted, following Orpheus Caledonius and Ramsay]

18

Leader Haughs and Yarrow

When Phoebus bright, the azure Skies

With golden Rays enlightneth,

He makes all Nature's beauties rise,

Herbs, Trees and Flowers he quickneth:

Amongst all those he makes his Choice,

And with Delight goes thorow,

With radient Beams and silver Streams,

Are Leader Haughs and Yarrow.

When Aries the Day and Night,

In equal length divideth,

Auld frosty Saturn takes his flight,

Nae langer he abideth:

Then Flora Queen, with Mantle green,

Casts aff her former Sorrow,

And vows to dwell with Ceres sell,

In Leader Haughs and Yarrow.

Pan playing on his aiten Reed,

And Shepherds him attending,

Do here resort, their Flocks to feed,

The Hills and Haughs commending;

With Cur and Kent upon the Bent,

Sing to the Sun, Good morrow,

And swear nae Fields mair Pleasures yield,

Than Leader Haughs and Yarrow.

An House there stands on Leader-side,

Surmounting my descriving, [describing

With Rooms sae rare, and Windows fair,

Like Dedalus' contriving:

Men passing by, do aften cry,

In sooth it hath nae Marrow;

It stands as sweet on Leader-side,

As Newark does on Yarrow.

A Mile below wha list to ride, [who desires

They'll hear the Mavis singing; [song-thrush

Into St. Leonard's Banks she'll bide,

Sweet birks her Head o'er hinging: [birch

The Lintwhite loud, and Progne proud, [linnet; swallow

With tuneful Throats and narrow,

Into St. Leonard's Banks they sing,

As sweetly as in Yarrow.

[a further seven verses]

20

The Lass of Peaty’s Mill

The Lass of Peaty's Mill,

So bonny, blyth and gay,

In spight of all my skill,

Hath stole my Heart away.

When tedding of the Hay

Bare-headed on the Green,

Love 'midst her Locks did play,

And wanton'd in her Een. [eyes

Her Arms, white, round and smooth,

Breasts rising in their Dawn,

To Age it would give Youth,

To press 'em with his Hand.

Thro' all my Spirits ran

An Extasy of Bliss,

When I such Sweetness fand

Wrapt in a balmy Kiss.

Without the help of Art,

Like Flowers which grace the Wild,

She did her Sweets impart,

When e'er she spoke or smil'd.

Her Looks they were so mild,

Free from affected Pride,

She me to Love beguil'd,

I wish'd her for my Bride.

Hoptoun's high Mountains fill,

Insur'd long Life and Health,

And Pleasures at my will;

I'd promise and fulfill,

That none but bonny she,

The Lass of Peaty's Mill,

Shou'd share the same wi' me.

photos © Marc Marnie

The other photos that didn't make it into the original CD booklet are these: Jamie MacDougall and David McGuinness both started at Hillhead Primary School in Glasgow in August 1971, and so have almost identical school photos, from different classes in the same year. Can you guess which is which?

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

![]() Late-baroque Italians try to sound Scottish, and their contemporaneous Scots try to sound Italian. A treat.

Late-baroque Italians try to sound Scottish, and their contemporaneous Scots try to sound Italian. A treat.![]()

Stephen Pettit - Records of the Year 2001 The Sunday Times

![]() Francesco Barsanti, born in Italy, lived and worked in Edinburgh for eight years. His better-known compatriot Francesco Geminiani didn't set foot in Scotland at all. Yet both were beguiled by Scottishness in music. The different styles and approaches of the Italian and (obscure) Scottish composers represented here pleads for the first few listens to be undertaken without following the track listings. Is this piece by a Scot trying to be Italian, or by an Italian trying to be a Scot? Is it Scottish with added Italian suavity, or Italian with a Scottish tang? The sublime - Barsanti's song arrangements, deftly inflected by Concerto Caledonia's players - rubs shoulders with the ridiculous - Lorenzo Bocchi's A Scots Cantata, the banality of whose guttural text is worthy of McGonagall. Everything is infectiously played and sung. Bizarre, but utterly compelling.

Francesco Barsanti, born in Italy, lived and worked in Edinburgh for eight years. His better-known compatriot Francesco Geminiani didn't set foot in Scotland at all. Yet both were beguiled by Scottishness in music. The different styles and approaches of the Italian and (obscure) Scottish composers represented here pleads for the first few listens to be undertaken without following the track listings. Is this piece by a Scot trying to be Italian, or by an Italian trying to be a Scot? Is it Scottish with added Italian suavity, or Italian with a Scottish tang? The sublime - Barsanti's song arrangements, deftly inflected by Concerto Caledonia's players - rubs shoulders with the ridiculous - Lorenzo Bocchi's A Scots Cantata, the banality of whose guttural text is worthy of McGonagall. Everything is infectiously played and sung. Bizarre, but utterly compelling.![]()

Stephen Pettitt - The Sunday Times

![]() What a charming collection this is. Concerto Caledonia explore the early 18th century vogue for Italian music that swept through Scotland and produced a "mongrel" hybrid of the "modern" baroque style of the south with the "ancient" airs of the north. There are no masterpieces here, but this disc is played with such infectious enthusiasm that the musical shortcomings become part of the enjoyment.

What a charming collection this is. Concerto Caledonia explore the early 18th century vogue for Italian music that swept through Scotland and produced a "mongrel" hybrid of the "modern" baroque style of the south with the "ancient" airs of the north. There are no masterpieces here, but this disc is played with such infectious enthusiasm that the musical shortcomings become part of the enjoyment.![]()

Andrew Clarke - The Independent ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Folk and art music have had a queasy relationship over the centuries but this is a delightful disc. The musical mongrel in question is half-Scots, half-Italian, and all Baroque: a peculiar beast who runs the gamut from what director David McGuinness affectionately calls "effective trash" to undeniable elegance across song settings, cantatas and folk inspired sonatas by Italophile Scots and Caledoniophile Italians. McGuinness's ensemble, indisputably Scotland's leading early music group, boasts excellent playing and is enhanced by winning performances from the vocal soloists. Fascinating.

Folk and art music have had a queasy relationship over the centuries but this is a delightful disc. The musical mongrel in question is half-Scots, half-Italian, and all Baroque: a peculiar beast who runs the gamut from what director David McGuinness affectionately calls "effective trash" to undeniable elegance across song settings, cantatas and folk inspired sonatas by Italophile Scots and Caledoniophile Italians. McGuinness's ensemble, indisputably Scotland's leading early music group, boasts excellent playing and is enhanced by winning performances from the vocal soloists. Fascinating.![]()

The Independent on Sunday